|

The triclinium, or dining room, took its name from the

three couches on which family members and their guests lounged

to take their meals.

Each couch was wide enough to accommodate three diners who

reclined on their left side on cushions while some household

slaves served multiple courses rushed out of the culina, or

kitchen and others entertained guests with music, song or

dance.

Marcus Vitruvius Pollio, in his book, de

Architectura, describes the triclinium: "The length of a

triclinium is to be double its breadth. The height of all

oblong rooms is thus regulated: add their length and breadth

together, of which take one half, and it will give the

dimension of the height. If, however, exedræ or oeci are

square, their height is equal to once and a half their width.

Pinacothecæ (picture rooms), as well as exedræ, should be of

large dimensions. The Corinthian tetrastyle and Egyptian oeci

(halls) are to be proportioned similarly to the triclinia, as

above described; but inasmuch as columns are used in them,

they are built of larger dimensions."

He goes on to direct the orientation of triclinia according

to the seasons: "Winter triclinia and baths are to face the

winter west, because the afternoon light is wanted in them;

and not less so because the setting sun casts its rays upon

them, and but its heat warms the aspect towards the evening

hours....Spring and autumn triclinia should be towards the

east, for then, if the windows be closed till the sun has

passed the meridian, they are cool at the time they are wanted

for use. Summer triclinia should be towards the north, because

that aspect, unlike others, is not heated during the summer

solstice, but, on account of being turned away from the course

of the sun, is always cool, and affords health and

refreshment."

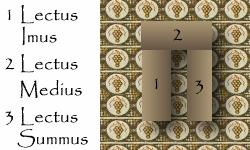

The social status of diners would immediately be apparent

upon entering the triclinium. Each of the three couches in the

triclinium carried significant social standing, as did the

three positions on the couch. The lectus imus was the master's

couch, and he assumed the locus summus. To his immediate right

was the locus medius, and farthest from him on the couch was

the locus imus. Members of the host's own family, if they

dined with him, usually reclined with him on this couch, which

held the least status.

Guests were positioned on the other two couches at the

master's discretion and according to their social standing. To

his immediate left was the lectus medius, and the third

position upon that couch, the locus imus, was the place of

honour, or locus consularis. The guest placed here had the

greatest access to the host.

References: Handbook to

Life in Ancient Rome, Lesley

Adkins and Roy A. Adkins (Oxford University Press, 1998); The

Romans, their Life and Customs, E. Guhl and W. Korner, Senate

Press, 1994

|